by Sarah J. Young

Sarah J. Young is a Senior Lecturer at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies at University College London. Her book, Dostoevsky’s ‘The Idiot’ and the Ethical Foundations of Narrative: Reading, Narrating, Scripting, was published in 2004. She blogs about her research on www.sarahjyoung.com and tweets on @Russianist.

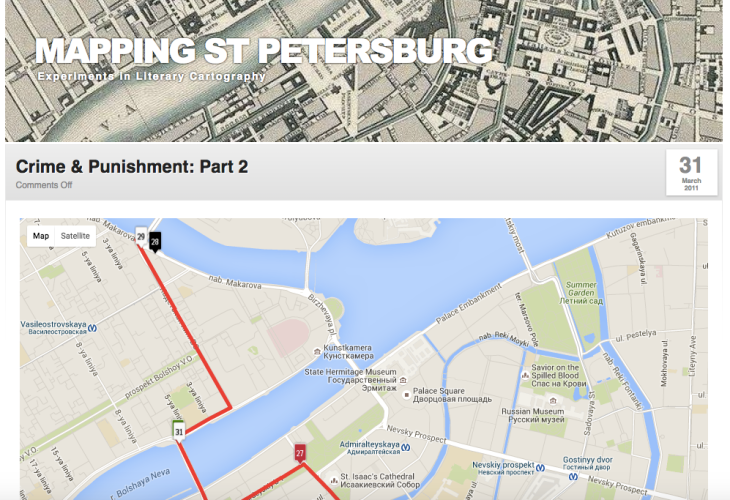

One thing that interests me is how digital technologies broaden the possibilities of what we can do as humanities scholars. My first foray into the digital, Mapping St Petersburg, used Google Maps to start exploring the interaction of text and city, and the ways in which the city’s spaces are incorporated into and transformed by its literary tradition. The results of that project, a set of interactive maps that enable us to interrogate the geographical dimensions of the ‘Petersburg text’, offer new perspectives that I have found very useful in rethinking the texts, and it has become a very useful teaching tool that enables students to engage with the text in new ways.

It’s no coincidence that we began Mapping St Petersburg with the same novel that we are now tweeting. The spatial and temporal specificity that enabled us to map Crime and Punishment so precisely – the extent to which it participates in and represents the real world of St Petersburg in 1865 – is one thing that makes it amenable to tweeting. But more than that, the novel’s very complexity and multi-layered nature invites us to break it down in different ways and construct new readings out of that process of granularization. This is in essence what we have always done as literary scholars, as interpretation inevitably involves selection (and therefore also exclusion) of material from the text.

Perhaps the main difference with projects like @RodionTweets and Mapping St Petersburg (in part because of their public nature) is that they force us towards completeness and to following our reading to its logical limit. While we may be concentrating only on one aspect of the text, we cannot lay aside any of the difficulties or contradictions that aspect may entail. I think we seldom have to be so consistent or thorough when it comes to traditional forms of interpretation (the advantage of the machine reading of Dostoevsky I’ve also recently embarked upon is similarly the complete overview it offers). The result of that process, for me, has been closer readings than I have ever done before, and these have revealed all sorts of details that I have never previously noticed. So it is perhaps not so much that these digital projects have allowed us to do something we couldn’t do before, rather that they have given us access to an augmented version of what we have previously done.

Writing this a few days before the tweeting of the present time of Crime and Punishment begins, I’m interested in the results as much as a reader of the novel as in my role as one of the participants in the project. As a reader, I wonder what impression the tweets will give of the text as a whole, and what new insights they will offer. Already from the tweets we have seen from the novel’s pre-history, I’m struck by how easily they fit into my timeline and become part of the echo-chamber (which gives me a certain insight into the accounts I follow), and the identification we (mainly the participants in the project) have been experiencing with Raskolnikov, as his problems seem not so very remote to our own:

As a participant, I wonder how my interpretation of Raskolnikov’s perception of events will differ from my colleagues’ when we see the tweets in situ. One thing I’ll be particularly interested in – which I really struggled with, and to which I’m only now, in retrospect, beginning to find an answer – is how the tweets deal with the other characters. We tend to think of Crime and Punishment as focusing solely on Raskolnikov, and to a great extent so it does. But for all his introspection, for large parts of the novel he interacts with others and in the first couple of parts at least he is very alive to the world around him on the streets of Petersburg. These elements of necessity appear in a more passive role than they play in the novel itself – still present, and perhaps with even more intensity, within Raskolnikov’s internal dialogue, to be sure, but their external part in that dialogue is removed, or at least refracted through Raskolnikov’s lens (I’m particularly looking forward to Marmeladov’s funeral from that point of view – and to what Jennifer Wilson has to say about writing the tweets for that part of the novel). That refraction undoubtedly provides a concentrated view of Raskolnikov’s perspective and thoughts about how he experiences the events of the novel, which in itself has the potential to reveal new and unexpected questions. But at the same time, twitter is an interactive platform, and while we can reply to @RodionTweets or incorporate his tweets into our own, Raskolnikov himself cannot interact in the same way either with other characters in the novel, or with the reading audience. I wonder in retrospect what it would look like if he could.

One of the questions we asked ourselves was: how would Raskolnikov use Twitter? The general consensus – with which I agreed – was that he probably wouldn’t tweet during conversations, but would give his thoughts on them after the event. Yet now (and I emphasize that this is several weeks after I completed the tweets for Part II and have had time to reflect on them), I can’t help thinking that some of those interactions could (would?) have been configured quite differently. For example, I can envisage Raskolnikov’s conversation with Zametov in the Crystal Palace tavern – one of the oddest scenes in the novel in terms of Raskolnikov’s behaviour towards another character and in the language he uses – being turned into an epic trolling session. I can see Porfiry doing the same later on. And if @RodionTweets’ followers replied to him, how would he respond? Perhaps that’s going too far in rewriting the novel (and indeed, would have turned this whole project into something quite different, on perhaps an unmanageably large scale), but such thought experiments can be helpful in our endless interrogation and reinterrogation of Dostoevsky’s characters, their relationships to each other, and our relationship to them. As with so many of readings of literature, I find that looking at what is not included is often as revealing as what is there.

This is Part 2 of a series of posts on the experience of creating @RodionTweets. You can follow the Twitter account here. The introduction to the series is here. Click here to read Part 1 or here to go on to Part 3. More information about the #CP150 project can be found here.

This post has been cross-posted on sarahjyoung.com and All the Russias blog.